I Was Dead and It Was Chris Killip’s Fault

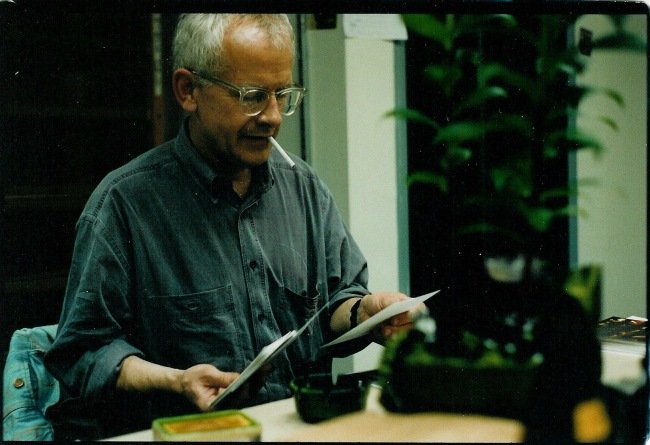

Chris Killip, Harvard darkroom, May 1993

I

I first took a photography seminar with Chris Killip when he was a visiting lecturer at Harvard.

It was my junior year at university, and I had just been officially admitted into the department of Visual and Environmental Studies (Harvard’s typically lofty name for what every other university calls an art department). It was the only honours-only department at Harvard, which meant we had to maintain a high grade point average, lest we be accused of painting pictures in place of doing rigorous term papers or something like that.

One of the smallest departments at Harvard, VES students were split across Carpenter Centre (the only North American building designed by Le Corbusier) and the basement of Sever Hall in the Yard, where advanced photography as well as film and animation classes were held. This is where I lived, it felt like, underground at Sever, for most of my time at Harvard.

Unlike his colleagues, and unusually for Harvard, Chris didn’t have endless degrees to his name. Moreover, he told us he’d dropped out of school at age 16. Committed to photography, he had quickly moved into the world of fashion photography, and was flown around the world at the behest of glossy magazines within a few short years.

It was while he was on his way to the Caribbean for one such assignment that he had a day’s layover in New York. He visited MoMA and saw an exhibition by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Seeing the power of documentary photography, he quit his job on the spot and moved back to his home town in the Isle of Man.

It must have been a stark contrast from Vogue photo shoots in the Bahamas to this economically challenged corner of the UK, home to a neglected fishing community. Chris told us stories of how mothers there didn’t teach their sons to swim, because if they fell over their fishing boats, it was better they drowned quickly as the harsh waters would always consume them whole.

The photos Chris took during those years were immortalised in two collections – Isle of Man: A Book about the Manx and, famously, In Flagrante.

II

Chris taught us how to take portraits. If we wanted the person to move, instead of giving instructions, we were to arrange ourselves in the pose, because human nature meant the subject would soon enough mirror our position.

He trained us to really see an image. This was an excruciating component of each class. He’d project a photograph by Martin Parr, for example, onto a large wall and have us analyse it. For hours. It took me ages to understand the purpose of this task – that we had to see beyond the obvious and really appraise the composition and frame, the light and shadow, the intention and the aim of each image. (Parr and other photographers dropped by our class when they were in town, a gift we oblivious students didn't quite appreciate; but then Al Pacino and Andy Garcia also came by our departments, so we were a bit blasé – as I've said elsewhere, education can be wasted on the young.)

We studied the greats, an education I’m grateful for to this day. I can tell a Weegee from a Lisette Model from a Garry Winogrand from a Robert Frank from a Helen Levitt from a Brassaï from ten paces. What I learnt from Chris about photography has been moulded into my brain’s very grooves for life.

He told us when he began to take photographs in the Isle of Man, he’d put his prints alongside those of his heroes’ – and brutally compare how far he had yet to go. He wanted us to train our eyes to understand and appreciate the world that could be captured through our camera lens.

III

Our seminar was small, and after the one lone man in it dropped out, it ended up being eight women. We were a diverse but dedicated group. Our final assignment was a project each of us would focus on for the last few months of the semester. Everyone else quickly found their respective subjects, but I kept bouncing around.

I went with my camera to Bangladeshi restaurants in the area but didn’t find much there. I photographed empty spaces for a spell but they just left me feeling… empty. I thought of capturing people as they awoke in the morning but after the first attempt of trying to stay awake (or get up early enough) and then to creep into someone’s room in order to do this wigged me out.

I went to Chris, saying I was stuck. We had a somewhat terse relationship. I felt at times he was harsher, more unforgiving, with me than with anyone else in the class, pushing me again and again, sometimes to the limits of my tolerance. It was a year later that he told me he did this because he knew I was capable of really saying something, if only I allowed myself to go there, and it was frustrating for him to see me hold myself back. (Fear, my old friend, still accompanies me to this day…)

So my going to him for help was admitting defeat, something my ego struggled with but I didn’t know what else to do. He said he had the perfect subject for me – it was completely accessible but one of the most difficult. I said I’d take it, whatever it was. He said: self portraits.

Blood rushed to my head. I hated being photographed! The thought of turning the camera onto myself felt like the most excruciating assignment ever. But Chris wouldn’t hear any excuses – I’d already accepted, he reminded me, now I had to go do it.

This was when my depression was getting worse. I had already been hospitalised once, and I was seeing a psychotherapist on a weekly (or if it was bad, twice weekly) basis. All I thought about all day – morbid as it sounds – was death and dying.

So I leaned right in: I photographed myself dead. And because I didn’t know how I could die (though I devoted all my hours to this eventuality), I wanted to see myself dead in as many ways as possible. (I shared some of the images on an earlier post.)

The project revitalised me. I embraced it as if it were my life’s mission. I stayed up all night to catch the early rays of sunlight for certain shots. I exhausted my resources trying to find the right locations and the best props. Self portraits being tricky to do alone, I enlisted my sister and close friends to help.

Chris, ever the tough taskmaster, said the images were not good enough. Photos of me dead were a gimmick. I had to be saying something. Was there a narrative?

The series eventually expanded to show an image of me dead and alive in each setting, the point of which now escapes me. There’s no question, though, that the dead images were the ones that struck a chord. My classmates and friends had great fun parodying the series, taking ‘death by camera’ pictures of themselves (strangled by the strap, stabbed by a lens, etc). Professors I didn’t know stopped me on corridors to tell me how much they responded to the photographs. A stranger even came up to me on the Boston subway two years later to say he was still haunted by the images of me dead.

IV

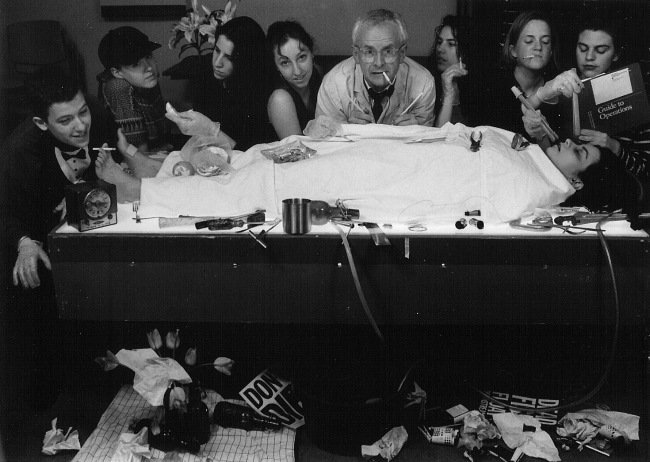

At the time of the seminar, my dedication to my project slightly helped improve the difficult equation I had with Chris. I had decided the first image of the series should be of me lying on an autopsy table, in order to ask the question: how did I die? And the rest of the images would attempt to explore the myriad ways I could.

I asked Chris to be the medical examiner for the image. I was amazed his reserved English formality softened enough to agree to my request. Not only that, he went out of his way to hunt down a white lab coat for the task and helped rearrange our little seminar room to create the set I needed. I designed and framed the shot, and had a fellow student click the shutter on my instructions as I lay dead on the table.

Unbeknownst to me (as I lay with my eyes shut), the ever correct Chris started to make funny faces into the camera. These being pre-digital times, I only discovered this when I developed the roll and printed the photos in the darkroom hours later. As the images crystallised on the developing tray, I cracked up, delighted to see this unexpectedly goofy side to him.

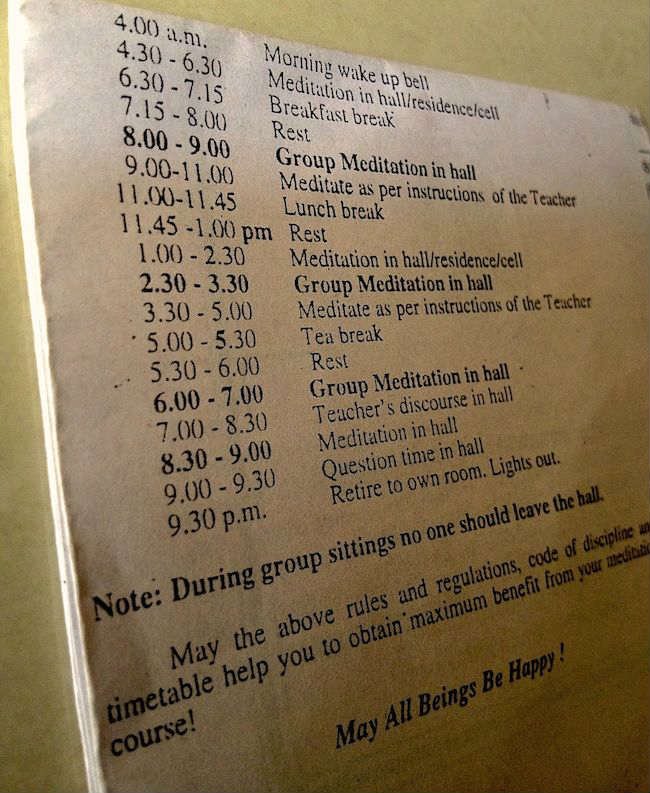

For the last few months of each semester, it was normal for photography and film students to spend the whole night working away in Sever basement. We would stay up until about 5am and then crash in various seminar rooms for an hour and half before waking up to make our way over to the Freshman Union when it opened for breakfast, laughing like hyenas from caffeine and sleep deprivation. Chris would arrive at 6.30am, well aware his students had been up the whole night, with fresh coffee and sometimes flowers for the darkroom.

The night I developed the images of Chris making a funny face, my classmates and I decided to print a number of these photos, cut out his face and hide them all over the darkroom.

We stuck his body on a carton of milk in the small fridge as if he was jumping out from behind it. We stuck his face in the lilies he’d brought in the day before. We put one over the Ilford box of photo paper we used, which showed a woman in her underwear. We put another over a beer bottle inside his office fridge. We hung a print from the drying line. We slid one in between the pages of a book in his room. In a very meta move, we put Chris's face on top of a parody a classmate had done of Chris's famous photograph, Youth on a Wall, which was on our bulletin board. We stuck them in every sneaky place we could think of.

Our meta move

Chris inserted all over the darkroom (photos taken when sleep deprived at 5am, then scanned years later, apologies for the poor quality)

Now, a few days before, another professor at Harvard had had an exhibition showing early 20th century family portraits of parents posing with their dead children, and other macabre moments when death and photography intersected.

Chris got a copy of the book from the exhibition to share with the class. I was unaware that Chris photocopied one of my dead photos, cut out my dead face from them, and attached them to Xeroxed images from the book and snuck them around the darkroom (sadly, no photos of these remain).

So somehow at exactly the same time, Chris and I pulled the same exact joke on each other, using each other’s funny/dead faces for the stunt. We both continued to find our own faces attached to random things in and around the darkroom for the rest of the semester (and, as he stayed on in the summer, throughout the summer for him too).

We took a class portrait around me lying dead on the autopsy table, May 1993

V

I did my undergraduate thesis in photography with Chris the following year, by which time he had become professor. I graduated in 1994 and stayed on in Boston for another six months, juggling three jobs to pay rent. One of them was in the Carpenter Centre darkroom, a position Chris was kind enough to arrange.

I saw him a few times over the next few years when I visited my sister in Boston. He became Chair of the department, and now had his office in Carpenter Centre. I was working in films, and thought I’d done well to move up in this exciting, glamorous world. I clearly still wanted his approval, but his reaction to my bravado and forced joviality was always inscrutable; I never knew quite what he made of any of it.

He had helped shape me in such a distinct way that I memorialised him in my fiction for years to come (though I didn’t tell him this; he would have rolled his eyes and made one of his usual dry yet acerbic remarks).

It was perhaps ten years after my graduation when I was flying from Boston back to London one time. Though my career was going well, I was at one of the lowest points of my life. I was deeply unhappy in my marriage, feeling trapped and like a failure. My health was at its nadir, with unexplained excruciating pain, feeling I was in an alien body, my face and body more bloated than ever before or since. I caught a glimpse of a familiar face many rows ahead retrieving his bags from the overhead cabin. I did a double take – it was Chris!

Then I saw myself, of what I had become. I had not overcome my fears to boldly tell my unique stories from the truest part of me. Instead, I was embodying all that could have gone wrong, and did. In my shame, I slunk out before he could see me, though I feel certain he did.

Then last year, at our 25th reunion, my roommate and I tried to see Chris but he had retired two years prior. As I was going to stay on in Boston for a bit longer to see my family, I got his number and tried to call, but was unable to connect with him.

VI

It was this morning that I received an email from my Harvard department informing us of his passing away a week ago. I had somehow missed the obituaries in the Guardian, the BBC, London Review of Books, Le Monde and all the global publications mourning the loss.

It made me pull up the images and memories, and write this to remember and honour Chris. Though he was at times undeniably tough on me, now that I’ve mentored many young people myself, I know it came from a place of wanting me to rise to the potential he saw in me. I know too that he always ultimately had my back, as he demonstrated time and again.

Sometimes, remembering the past gives us a chance to reevaluate the present. I don’t believe I was a terribly good photographer, and it was right for me to stop. But I also know that photography is merely a medium, and the medium ultimately doesn’t matter – what matters is the vital need we humans have to be creative and to tell our truth.

Chris knew at age 26 that a lifetime spent doing glossy commercial work was not his calling, and was brave enough to change his life to attend to what was. And despite the incredibly vast and valuable education I received from him, it is perhaps this that I think of the most now.

I know it’s time to stand up to that old foe, fear. To go ahead and create away. Because each of us tell unique stories, and that is what we are remembered by – but only if we overcome the terror of sharing them from the truest place we have inside.

Chris Killip, born 11 July 1946, died 13 October 2020.

Chris in the darkroom, May 1993