Three Things I Learnt From Working With a Terrible Boss

‘There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all.’

— Peter Drucker

I had this boss once. He juggled multiple businesses in various countries so he was always on the move. When stuck in traffic, he utilised the time to record messages into his phone to be transcribed into emails. His head assistant delegated the task among four secretaries (there were a lot of emails).

My colleagues and I received these missives from his assistants at 2am. Because he often worked around the clock, so did the people around him. One of his most frequent boasts was how he only needed three hours of sleep a night.

He restructured the company every few weeks, his ambition at times expanded to include what took giant media conglomerates decades to build – elaborate studios, hotel facilities, a museum and theme park. Other times he blamed us for failing to meet his targets and changed his plans back again.

He frequently reimagined the vision of the company. I received hand drawn diagrams he scribbled on long flights then photographed to send me when he landed. The ethos shifted so often that filmmakers were confused if we were looking for tiny budget/big impact stories, or looking only at tentpole projects, or just alternative niche voices that would do the festival rounds.

He blew into town for a day now and then, making us line up a dozen meetings back to back in order to squeeze every second out of his schedule. On a Sunday.

He gave me and the other department heads a lot of responsibility but held on to the authority himself, frequently backtracking on his written approvals. Getting his sign off, therefore, meant absolutely nothing. One time (actually more than one time), my colleagues were forced to renegotiate the same deal with a filmmaker 12 times because our boss fretted that if the other party actually agreed to the terms each time, it meant he – our boss – had been taken advantage of.

He micro-managed, wanting to be involved in casual meetings, baffling those outside the company as to why a chairman was pointing out typos on a rough draft when the purpose of the meeting was to decide if the story was worth telling in the first place.

My colleagues and I became used to repeating ourselves when dealing with him, because his two eyes were often trying to take in four different things at the same time. Once he rang me and launched into one of his usual rants. When I asked about another voice I could hear, he dismissed it, saying it was only the bus tour guide talking. Because, yes, he was on a tour bus, with his family, on their holiday abroad. And while he was sitting in front of the poor guide and talking loudly to me on his phone, he was also fielding other calls on his other mobile.

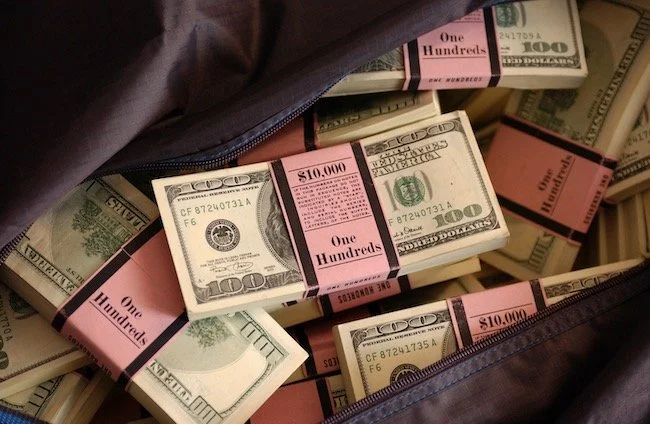

He constantly criticised everyone for never working as hard as he did, even though we too often had to slave around the clock and on weekends. He complained all of us were incompetent, unproductive and basically getting free money because he was the one doing everything. I was not the only person who had a breakdown in the middle of a workday. The staff turnover at the company was insanely high. He exhausted everyone.

One time he doctored my emails and forwarded them to a third party. Upon discovering this, I was shaking with anger. When I told him what he did was illegal, he shook his head at me and said I had to stop being so British.

One good thing to have come out of this whole experience is that I can now sum up for you three (of arguably many) lessons I learnt from working with this man.

Choose one

While I was still in this job, I read a book on productivity by Greg McKeon called Essentialism. In it, McKeon described my boss exactly – as a Non-Essentialist.

Non-Essentialists, McKeon explains, are people who have the worst possible approach to all matters. They think that making things better means adding something; they think one hour less of sleep equals to one more hour of productivity; they take on too much and work suffers; they pursue a straddled strategy where everything is a priority.

The book held up a mirror to my boss. But he was an extreme and oblivious version of me. And if he was to serve as a cautionary tale, then I had to change the way I operated as well.I too used to sleep just three hours a night during a shoot. I’d fall sick and refuse to take time off, thinking work couldn’t go on without me. And most of all, I loved having lots of balls in the air, convinced the adrenalin from juggling them all somehow made me work more efficiently, when in fact it just diluted the focus, effort and results.

First lesson: be discerning about what’s vital, and focus on one thing at a time.

Lower the noise

When I first joined the company, I believed my boss was Very Busy Doing Important Things. I soon realised that his busyness was just noise. He actually did nothing.

Life coach Brooke Castillo outlines the differences between passive action and massive action in this episode of The Life Coach School podcast.

Passive action can give the impression of accomplishing things when we are busy reading, researching, preparing and so on. But in actuality, we’re only consuming.

Massive action is when we are actually doing things, and this means we’re creating.

If it feels unclear which one is which, Castillo says passive action involves no real risk. Massive action definitely does, because we’re putting ourselves out there.

When I think of this in terms of my former boss, it makes perfect sense: he was terrified to take actual risks, so he simply changed his strategy or rejected everything. There was an exhaustive amount of passive action, but zero real action.

In my own way, I too can convince myself I'm being productive, when I'm just being busy. When I get anxious, I focus on clearing the decks, as I call it. I get rid of the niggling chores that crowd my head, such as dealing with tax authorities, or fixing technical glitches on my websites. It’s not that these tasks should be ignored, but I often let them take centre stage and keep the meaningful work ‘for later’.

Second lesson: take creative risks instead of staying (safer) in consumption.

He’s not going to change

While I was doing this job, I would go regularly to a therapist who did Reiki and various other body healing modalities. Though she was not a psychiatrist, I would start each session venting about my boss for five minutes just to decompress, then she’d help me work through my anger/frustration/misery over it.

I felt trapped because my visa was dependent on this job, and I wanted to stay on in this country, and I felt my skillset was quite niche, and most companies couldn’t afford me (I had a long list of reasons).

This therapist, after hearing me fume about ‘my boss’ every week for months, somehow put two and two together and figured out who I was talking about (he’s well known). She had dealt with him on several occasions (not as a client) and had a sense of who he was.

This was how she framed her question to me: this man operates on a very low frequency. And I have worked very hard to elevate mine. He is incapable of raising his energy to higher than where he is. If I want to deal with him, I have to stoop to his level. Is this a price I am willing to pay?

And while I could make the case for needing a visa or salary, I couldn’t argue against, well, evolution. I had worked really hard to process many of my own demons; I was not willing to regress. The psychological toll had already been hefty, and that came from the conflict I felt by bending myself to conform to his warped beliefs and practices.

This really helped me give myself permission to get out.

Third lesson: don’t compromise who you are in order to fit around someone else.

These lessons continue to serve me well, though I'm somewhat dismayed that they were not things I learnt once and immediately assimilated.

Even in the past few weeks, I had to remind myself to focus on one big project at a time (my insecurities make me dash from one thing to another, for fear of choosing the wrong one).

And though I feel triumphant when I tick off items from my to–do list, I have to ask if I want my epitaph to be ‘she was always on top of her chores’ or, you know, something more meaningful.

Like so many valuable teachings, they are a practice. So I continue to bump up against them. But that's okay. I'm glad to have the awareness at least. Because the version that carries on, oblivious, is truly terrible.

‘They deem me mad because I will not sell my days for gold, and I deem them mad because they think my days have a price.’

— Kahlil Gibran

Related Recommendations

My favourite antidote to any toxic person – whether in the news or in memories, as above – is brilliant Michelle. Because there is nobody else who combines grace, wisdom, wit, power and exquisite authenticity like Michelle Obama. She is simply the best. Hearing, reading or watching her teaches me to have courage, hope and humility.

Michelle Obama’s extraordinary memoir, Becoming, became the bestselling book of 2018, breaking the record in just 15 days. It’s been translated into 24 languages, and is the bestselling memoir in the US of all time.

There’s the Netflix feature documentary, also called Becoming, that follows her on the book tour. It doesn’t go deep, but it still made me tear up with gratitude for all she is.

One of my favourite interviews with her is this two-parter with Oprah on her SuperSoul Conversations podcast, also titled, yes, Becoming. The first episode covers her childhood, and in the second episode, Obama speaks frankly about going to marriage counselling and the difficulties she faced in the early years of her marriage.